Book Chapters

How Periyar’s Self-Respect Movement Shaped Tamil Identity in Singapore

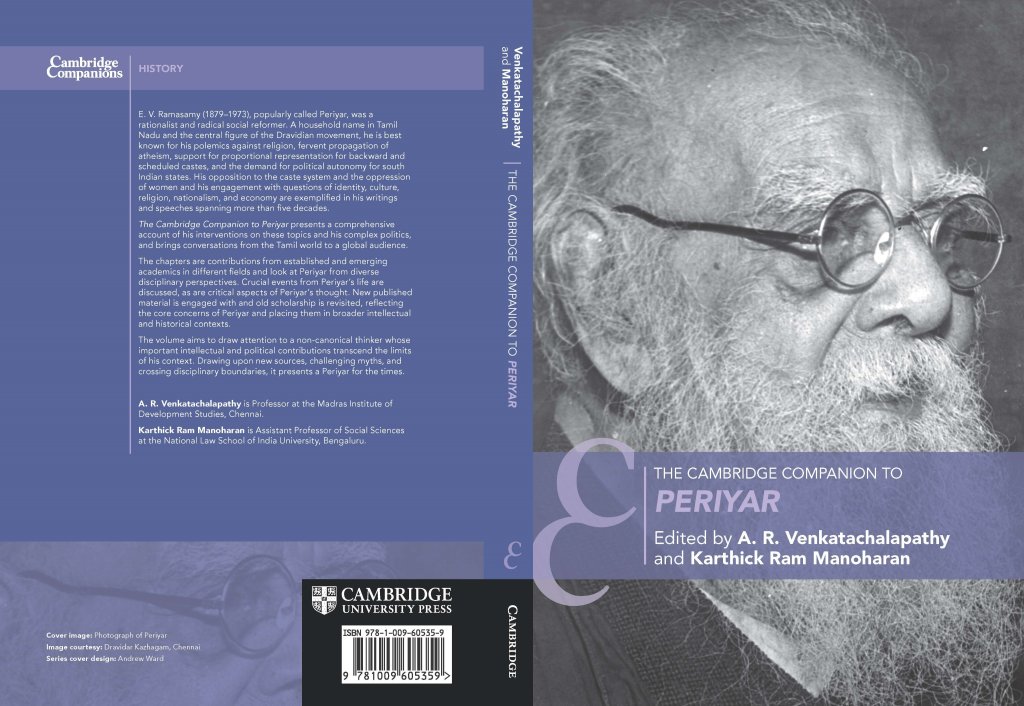

When we think of Tamil communities in Southeast Asia, stories of migration and trade, or conversely, of division and displacement, often come to mind. But there’s another story—one that’s just as powerful: the impact of E.V. Ramasamy Periyar and his radical Self-Respect Movement.

Periyar’s fiery rejection of caste and push for equality didn’t stop at the boundaries of the Madras Presidency. His visits to Southeast Asia during the late colonial period lit a spark in the diaspora.

Without state support, Tamils in Singapore turned to Periyar’s ideas as a model for self-strengthening. The Self-Respect ethos became a grassroots engine for change and a bold reimagining of Tamil identity. Tamil wasn’t just a mother tongue; it became a language of dignity, justice, and modern thinking.

The spirit of Self-Respect crossed the borders of time and space to unite the community, giving it the tools to organise, speak out, and claim its place—not as second-class citizens, but as equals among equals in Singapore.

Peer-Reviewed Articles

Neera vs Toddy (and Tea): How a Palm Drink Became a Political Statement in Colonial India

During the interwar years, India’s freedom struggle wasn’t just about throwing off the British—it was also about what one ate and drank. While the British pushed tea as their temperance-friendly solution, Indian nationalists had another idea: neera.

Fresh, unfermented sap from the palm tree, neera was marketed by Congress leaders as the perfect swadeshi (indigenous) drink. It was pure, nutritious, and most importantly—not toddy. For the largely upper-caste Congress leadership, this distinction mattered.

It wasn’t just about purity. Promoters of neera saw it as opening a path to social reform and rural economic revival. They highlighted its health benefits and the potential to support jaggery (gur) production. Better yet, neera could offer a new livelihood for palm tappers left jobless by prohibition.

Sounds ideal, right? Not quite.

The push for neera ran into a stubborn reality: people still liked toddy, particularly in the context of prohibition. Trying to tame the toddy market proved harder than Congress leaders had anticipated. Plus, producing and preserving neera on a large scale proved a logistical nightmare.

The drink may have been pure, but removing deeply rooted traditions? As the nationalists were to find out, this was easier said than done.

Race, Class Power: The politics of a working-class alcohol in Singapore

In colonial Singapore, a widely-accessible palm drink—toddy—sat at the centre of a much bigger story about race, class, and power.

Cheap, mildly alcoholic, and made from fermented palm sap, toddy was the go-to choice for exhausted workers after long shifts in docks, plantations, and construction sites.

But colonial authorities didn’t just tolerate toddy—they managed it. Seen as a “lesser evil” compared to hard liquor or opium, toddy was dispensed in state-run shops, regulated to keep workers content, but still productive. Productivity, after all, came first.

These toddy shops were more than watering holes—they were social hubs. Labourers would socialise and unwind in spaces that were unmistakably theirs. Over time, they were pushed to the peripheries of urban life— too noisy, too dirty, too Tamil for colonial society.

By the 1950s, things took a darker turn. Gangsters muscled into the toddy trade, and public health concerns and moral panic followed. Despite toddy’s wartime boom and even its use as medicine, the drink’s days were numbered. By the late 1970s, toddy shops in Singapore were shut down for good.

Today, the story of toddy in Singapore shows us that even the humblest drink can reflect enduring issues of labour, racial stereotyping, and governmentality.

EV Ramasamy Periyar first visited Malaya in 1929, setting in motion a series of events that would have far-reaching repercussions for how Tamils in Malaysia and Singapore would subsequently engage with politics.

The radical campaign of Self-Respect rejected caste, questioned religion, opposed patriarchy, and demanded dignity for all, regardless of the circumstances of birth.

Through Tamil-language newspapers and community self-help associations, the Self-Respect Movement gave Malayan Tamils a new political voice. Not just as colonial subjects or coolies, but as people with pride and purpose.

Across the Bay of Bengal, Tamil migrants made the message of Self-Respect their own, even forming volunteer brigades protesting Hindi imposition in the Madras Presidency subsequently.