Cultures of Control & Resistance

“…alcoholic beverages made using traditional methods and local ingredients supplied by the country…”

Country liquor – heard of it? Also known as indigenous liquor, the term refers to alcoholic beverages made using traditional methods and local ingredients supplied by “the country.” Everyday items used in cooking – jaggery, molasses, and grains like rice – or commonly found in nature – flowers, fruit, and certain types of tree bark – go into preparing country liquor.

“…an integral part of cultural traditions and economic systems around the world…”

Whether fermented or distilled, country liquor forms an integral part of cultural traditions and economic systems around the world. From chicha in South America to the African akepetshie and sorghum beer, to arrack in Asia, these brews do more than intoxicate. A source of livelihood to the communities that depend on them, they represent conviviality, community, and identity across cultures.

In India, there are many types of country liquor – desi daru, whether we think in terms of fermented drinks like tari (toddy), feni (fenny), sonti soru, and mahua, or distilled varieties like arrack, bangla, and tharra.

Country liquor is deeply entangled with caste and class in India. Typically consumed by people of lower socio-economic status, both urban and rural, traditional liquor brewing is a hereditary occupation for several Dalit and Adivasi communities.

“…country liquor is deeply entangled with caste and class in India…”

Examined through a political lens, the regulation of desi daru often emerges as a site of deep-seated tension. Despite their long histories and connections to tradition, they frequently straddle the margins of legality. In fact, several are illegal, having been pushed underground over time.

“…desi daru… a site of deep-seated tension…”

Brewers face constant criminalisation as country liquor production is, by definition, decentralised, prompting official concern about their regulation. Motivated as much by the problem of preventing adulteration as by the fiscal interest of bringing these industries under the state’s administrative and taxation frameworks, governments have historically vacillated between promoting and banning country liquor. The communities involved in producing these liquor varieties have often resisted state policies, thus rendering regulation a site of ongoing contestation between authorities and non-elite groups.

The Indian-made foreign liquor (IMFL) industry rarely faces the same scrutiny, even though it can also be and – at times, has been – affected by quality lapses. The checks and balances these varieties undergo are factored into their pricing, and the “entrepreneurs” involved in the production of IMFL benefit from state-issued liquor licenses and contracts, thus occupying the legal high ground. The country liquor industry, on the other hand, is frequently subject to police harassment and moral panic.

While enabling the powerful to consolidate their wealth and influence, the state’s regulatory frameworks often become implicated in the assertion of rights and agency by subaltern groups.

“Why the double standards?”

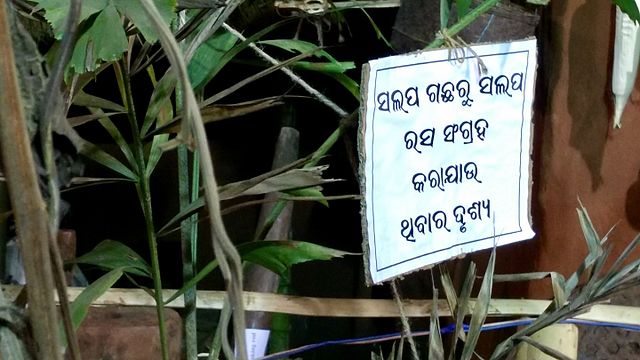

Since 2006, the Tamil Nadu Toddy Movement (TNTM) has been protesting the ban on toddy in the state of Tamil Nadu. The fermented alcohol has been banned since 1987, while IMFL flourishes under state patronage through TASMAC. “Why the double standards?” asks TNTM chief, C. Nallasamy.

Similarly, the reprisal was unrelenting in Chhattisgarh when the 2011 amendment to the state’s Excise Act lowered the amount of liquor the Adivasis could possess without a license. Grassroots activism, advocacy for tribal rights, and a legal review of the criminal charges lodged against Adivasis followed.

In Madhya Pradesh, the government is attempting to market mahua as “Heritage Liquor,” with labels such as Mond and Mohulo, the first mahua spirits in India distilled by Indigenous people, coming to the market in 2021.

“…tightrope between regulation and over-regulation…”

Governments find themselves walking a tightrope between regulating and over-regulating country liquor — the latter inducing the illicit production of liquor, often with deadly consequences. When regulation becomes too stringent, country liquor production is pushed underground, as it did in 2020, when more than 100 people died after drinking noxious liquor in Punjab.

Today, we see a trend of celebrating artisanal or craft beer and the like under labels like “organic” or “small-batch” in the West. This may prompt the question of whether beer is also considered a form of country liquor.

The question, however, really ought to be why certain products – and the traditions they represent – enjoy legal protection, market access, and elite consumer interest, whilst others remain stigmatised, criminalised, and heavily policed.

This would point us in the direction of power differentials that have become entrenched in society over time.

References:

- C. Nallasamy, [“Kal thadai seiya pada vendiya bothai porula?”] “Is Toddy a Drug that should be Banned?” Chennai: Farmers Press, 2019.

- Gerry Stimson, Marcus Grant, Marie Choquet, Preston Garrison eds. Drinking in Context: Patterns, Interventions, and Partnerships. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2013.

- Pranjali Bandhu, T.G. Jacob, Encountering the Adivasi Question South Indian Narratives. New Delhi: Studera Press, 2019.

Links:

Leave a comment